As CODE 04 approaches, we speak with contributing artist Bryan McGovern Wilson and his peer Cameron Klavsen, exploring how physics might appear if mathematics were to take form as sculpture and visual art. In this next peer-to-peer, the two artists elaborate their perspectives on quantum theory through abstract thought, diagrams and sculptures.

Vanessa Barros Andrade:

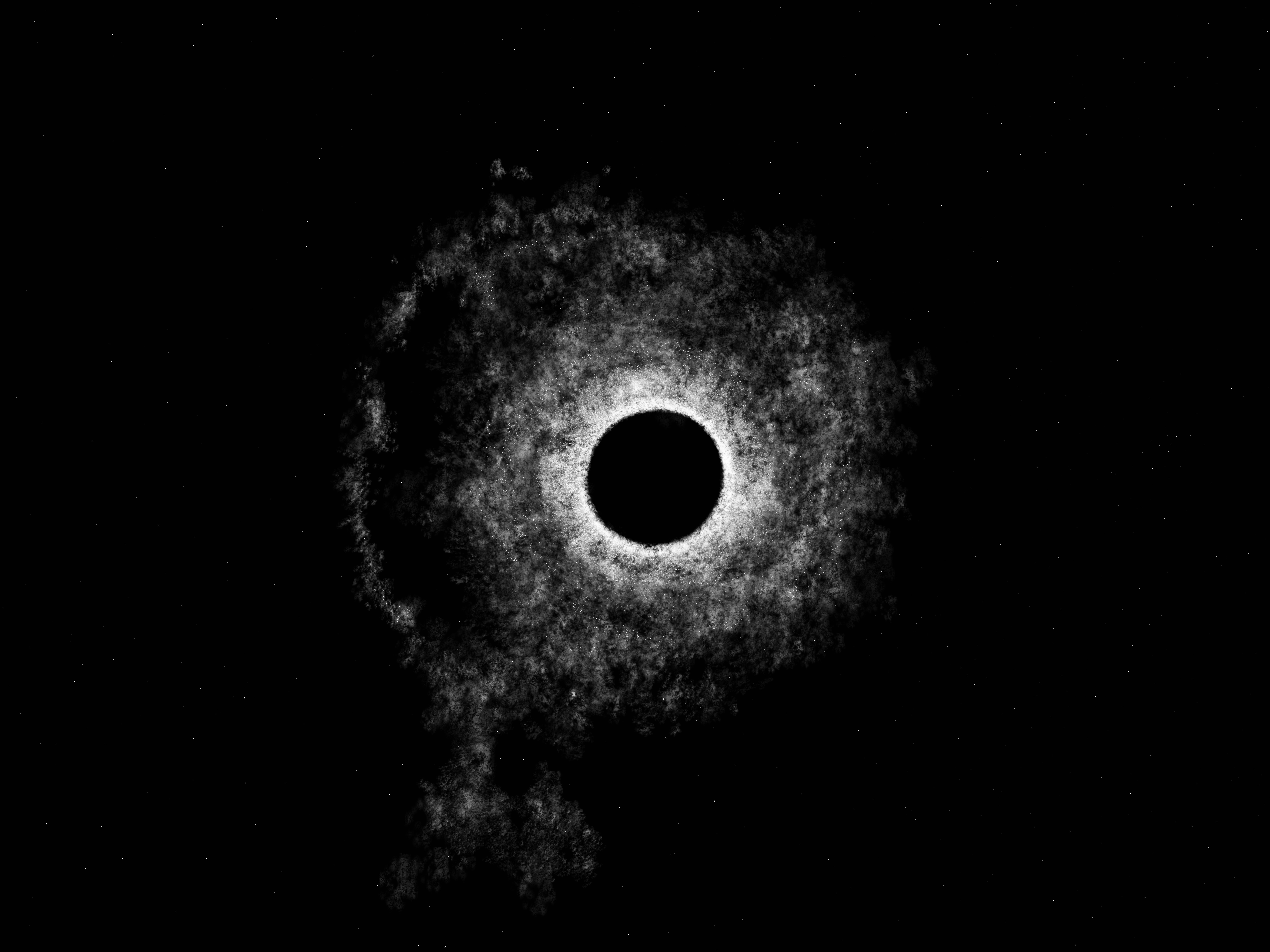

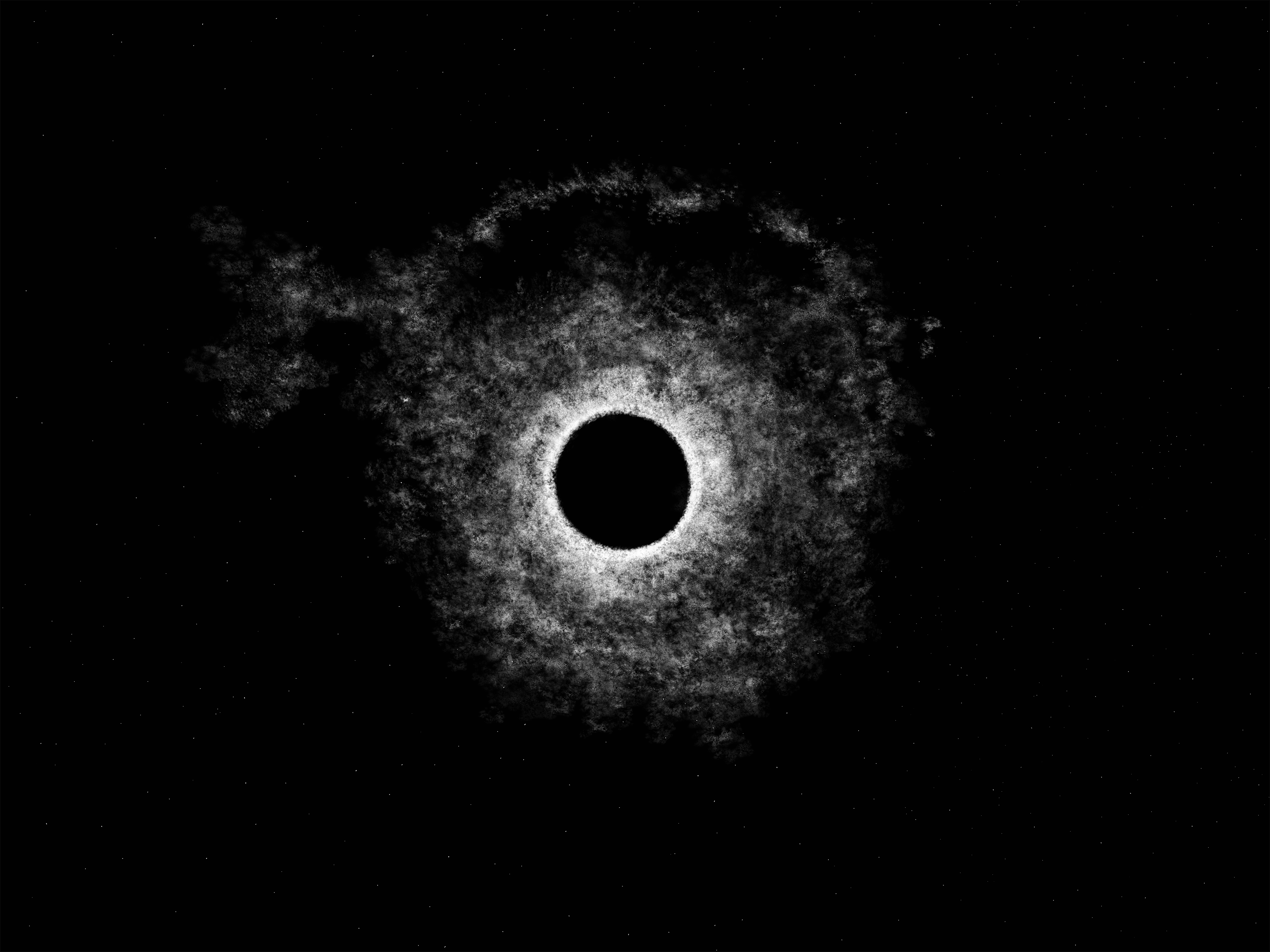

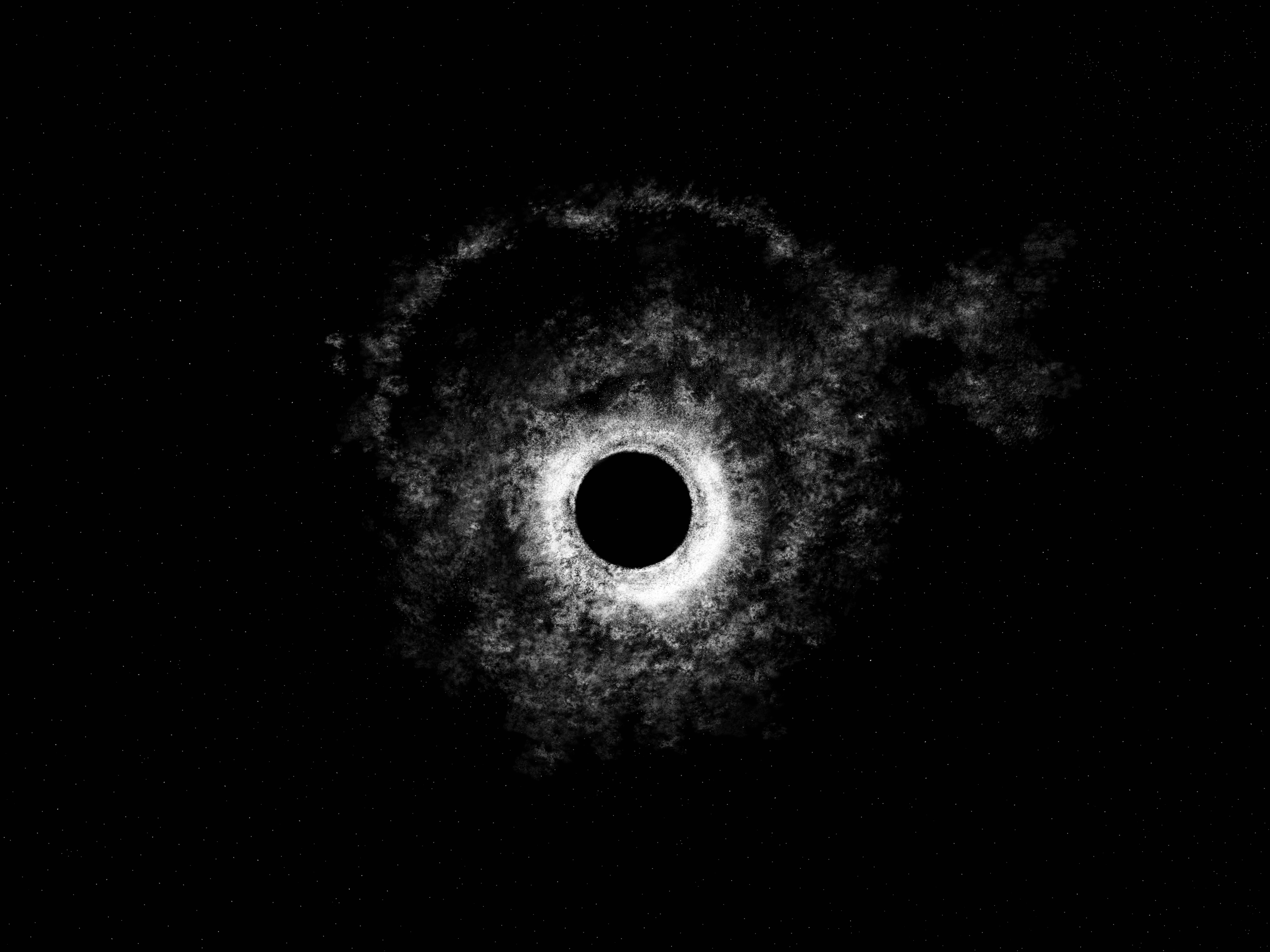

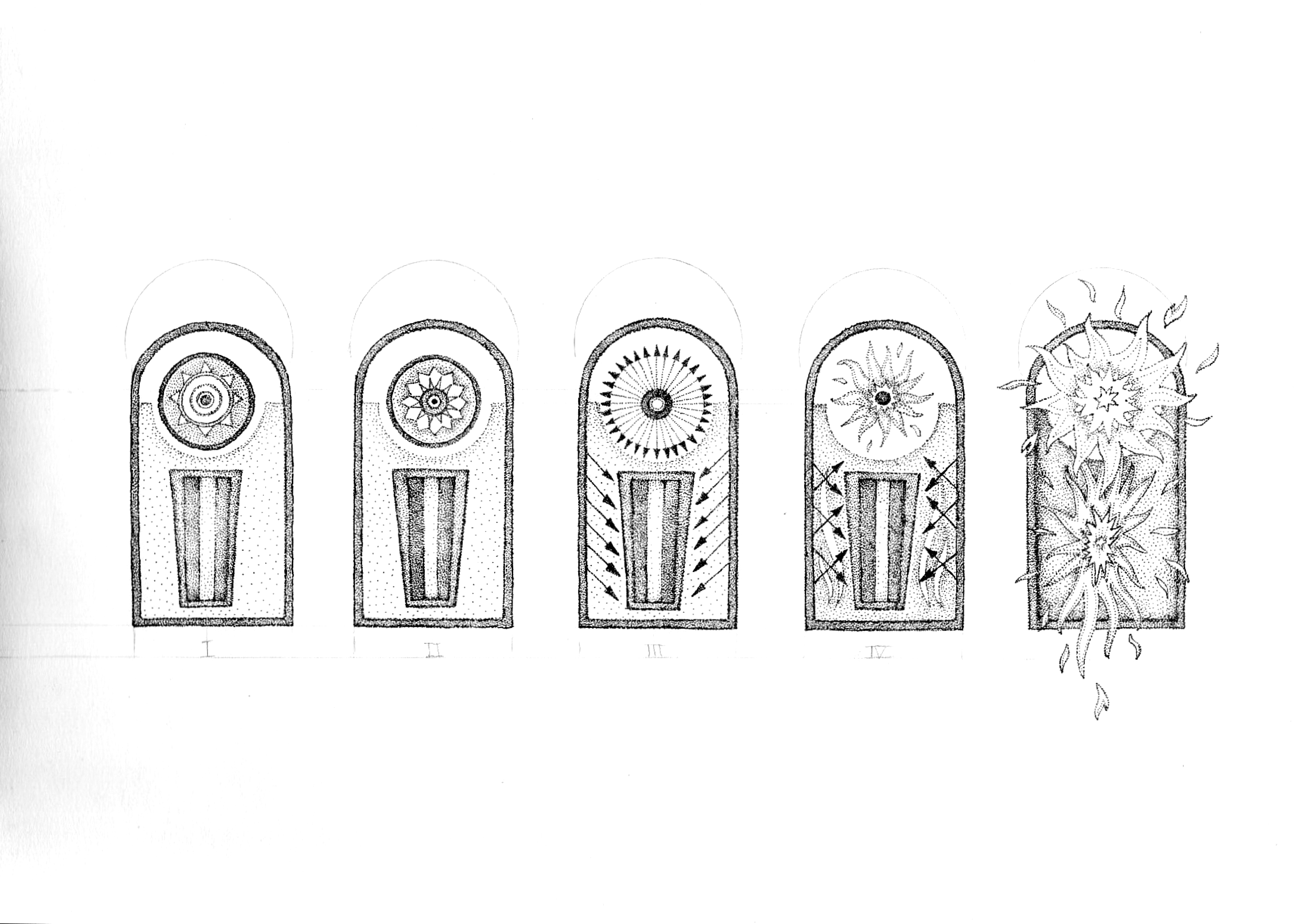

Cameron, can you explain your symmetry studies work? The illustrations

resemble the kind of visuals often seen in science literature. Do you create

them using AI? According to our research, AI has difficulty producing symmetry

because it generates images locally, pixel by pixel, rather than from a

top-down, holistic understanding of geometry. Can you share a bit about

your process?

Cameron Klavsen:

All of my work passes through a computer graphics program called, SideFX:

Houdini. It’s primarily used in film; think of an alien ship coming out

of an ocean, planet explosions, something catching on fire and so on. It's

a program used primarily for that. I like to use it for purposes other

than what it was intended for. I want to use the simulation for its failures.

What you're actually seeing in the symmetry studies are 3D portrait scans

I took of different people. It’s the image folding into itself and the

different axes getting turned into two dimensions like a contour drawing.

I’m interested in folding as a formal gesture. The particles are given

the goal to become an image of the person, but they never quite get there

because they bump into each other and there’s too much chaos. Essentially,

it’s a failure to represent reality. I like to use 3D simulation to see

what you can do with physics when you're not trying to emulate anything

perfectly. No AI was used.

Bryan McGovern Wilson: I think Cameron and I are both interested in using these types of programs in ‘the wrong way’. Unexpected things happen by approaching it this way and we aren’t set rigid parametres. There’s a process of discovery that happens and we give the machines some of the agency.

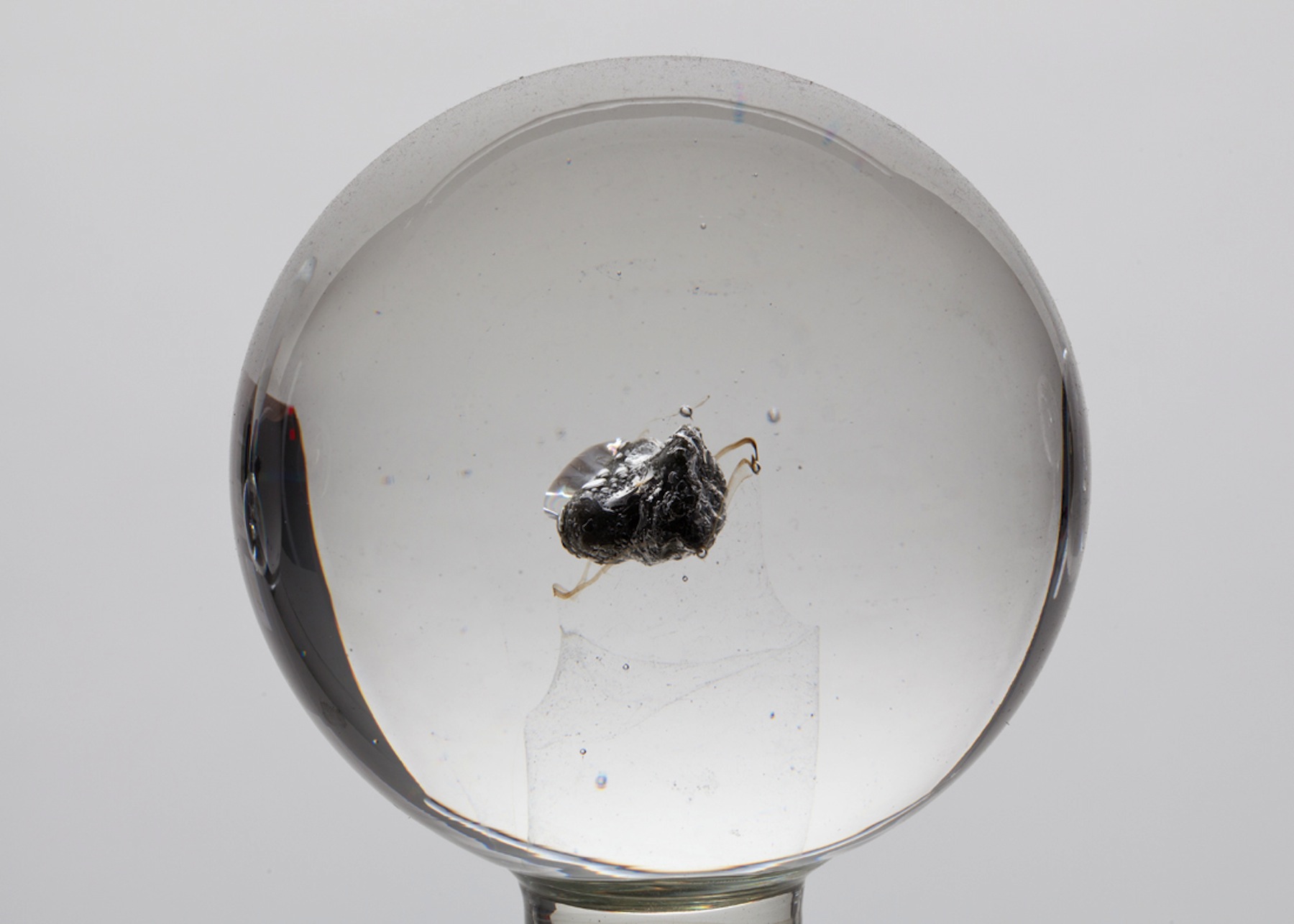

CK: I‘m writing bits of code, but then there are so many conditions which don't allow it to really be fulfilled, often because the amount of information becomes too unwieldy to process. It’s a lot about guiding the chaos. It’s something which can't even be sketched before it actually happens. I like doing this with sculpture too. All of the sculptures I make have a component that starts out as animation. I set up a moving situation and then choose a moment that is turned into a sculpture. These objects are like single moments frozen in time. It’s a collaboration with the lack-of-control itself.

BMW: You know pareidolia? That human impulse to project a face onto something symmetrical but also not quite like us? [That’s what I see us doing with math] It isn’t bodily, but abstracted.

CK: The vector fields in the programs I work with, and the equations that can operate within them are themselves simplifications of what we actually experience. We simplify physics so we can understand it. That’s what mathematics is in itself. It’s the longstanding question, ‘Is mathematics created or is it fundamental?’ I think it’s an abstraction of our reality. It’s also a distraction.

BMW:

I do think math is a language. There are visual languages, written, spoken,

musical—it’s a way of giving form to reality. In that way, the phrase "folklore

of math" is something I’ve been thinking about for a few years now. There

are only certain kinds of stories which can be told through the language

of math and it satisfies a certain aspect of our reality so we can get

closer to a common understanding collectively.

There are statements math makes which are true but denatured from the

senses. I’m not trained in math or physics or the hard sciences, but for

as long as I can remember I’ve been haunted by them.

CK:

I almost regret not having a background in math or physics because I work

on the computer so much and I’ve had to relearn a lot of math I thought

I really would never use. Now I’m trying to read papers on simulation and

figure out how to mimic these things.

On the other hand, a book that I think about a lot is Native Science by

Gregory Cajete. It focuses on how Indigenous thought has encompassed scientific

and mathematical concepts outside the Western traditions. It explains how

reality is just as complex and valid even though it's not coming from a

place of measuring. I think about science as a religion or playing the

role religion has in other times and cultures. Everything we do is explained

through science—for instance, what a plastic water bottle means, both in

an understanding of how it’s made and its environmental impact, and so

on. But if you gave that same object to someone from another culture or

time period, they might explain its existence in an entirely different

way.

BMW: I think what we identify as science privileges a certain amount of verification, it’s a reductionist or a materialist approach. There is utility in it, but it’s also convenient. The folklore of math is a way of apprehending aspects of our reality that are too overwhelming for us to understand. There’s so much that’s filtered through us and through animals and through objects. It’s obvious that we are projecting ourselves onto the universe and the world and we are only experiencing it through the human mind. But there are so many radically different ways of seeing or experiencing reality. This idea of ‘knowing’ [the truth about the universe] feels a little overrated.

CK: We believe the world is structured because we project that structure onto it.

BMW: Exactly! And a lot of math is digestible models. A lens that allows you to focus on reality as perceived by the human mind. The inherent bias is that no matter how deeply we probe into the subatomic or the farthest reaches of the universe, we are, by definition, always confronted with the human.

CK: Most myths see chaos as the progenitor of all things and I love that science does that too, now. We want to have knowledge of all things because it’s comforting—that's why I see science as a religion. Science offers meaning and a promise to provide order. Knowing that the world can be made intelligible and categorised feels nice. Then art comes in and finds the areas where the gaps aren’t filled. Artists push at the boundaries of truth while still being in that same system of belief.

BMW: I want to complicate that sentiment and say a lot of scientific disciplines and even artists are unified in that curiosity of framing things. Both have uneasiness baked in. The result might not always be for us.

VBA: Human thought itself generates synthetic objects. How do we draw the line between what is synthetic and what is not?

CK:

I do not believe in a synthetic versus natural binary. I actively try

not to use the word “nature” or “natural”. It’s influenced by our writer

friend Alex A. Jones. She says, “Nature doesn’t really mean anything, but

it reinforces an implied binary of the unnatural.” I think a lot about

how technology isn’t separate from us. It’s like another evolutionary layer,

or its own co-evolving life form. In Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, there’s this

idea of a distant form of being whose will or sentience we can’t comprehend,

and so we perceive it as lifeless.

Another example of that is in this anime Kill La Kill. Partway through

the series it’s revealed that clothing is sentient and has a form of intelligence

and it operates through humans with its own goals. This isn’t to say I

think technology is sentient, but rather maybe we are more controlled and

have been changed more by technology than we can control.

BMW: I live by the phrase, ‘nothing is not nature’. I think that we are all part of a unified field of some kind and that field is one of many. We are governed by forces and models we understand intuitively and observe fractionally but the totality is forever incomplete. That’s the antagonism I have towards ‘knowing or having the answer’. To me, it sells reality short. At best it’s a fairytale, and at worst it operates as a system of control.